Inheritance in object-oriented design can be a useful concept for organizing code and reusing functionality. At its core, inheritance allows a new class to derive properties and behaviors from an existing class which allows reusing functionality without duplicating it. By inheriting from a base class, the subclass automatically gains access to all the parent's public and protected methods and fields. For instance, a Chicken class could inherit from a Bird class that defines methods for flying and laying eggs that are common to all birds.

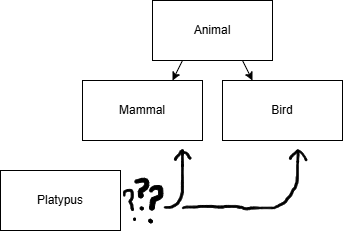

Standard inheritance like this can lead to categorization dilemmas also seen in taxonomic classification structures in other fields, when you need to model something like a platypus that uses properties and behaviors from more than one parent class. In this case you would need to select one class to be the parent and reimplement behaviors needed from the other possible parent class, leading to code duplication - ugh!

### Implementation with standard inheritance

class Bird:

def lay(self):

print("laid egg")

class Mammal:

def pet(self):

print("petting fuzzy animal, aw...")

class Platypus(Mammal):

# CODE DUPLICATION!!! >:(

def lay(self):

print("laid egg")

platy = Platypus()

platy.pet() #petting fuzzy animal

platy.lay() #laid egg

print(f"Platypus is a Mammal: {isinstance(platy, Mammal)}") #true

print(f"Platypus is a Bird: {isinstance(platy, Bird)}") #falseThis occurs frequently in industry when features are added to one class hierarchy and then need to be added to another later. Therefore, some standard approaches have been developed to handle sharing functionality outside of strict class hierarchies. Composition with dependency injection is the most popular approach and it is good practice to build features with composition instead of inheritance when possible. Several languages, including Python, also support multiple inheritance, where a class can inherit from multiple parents, adopting some properties of each.

Multiple Inheritance

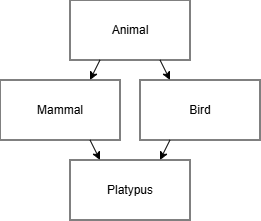

In languages that support multiple inheritance, there is a direct way to model a class that needs functionality from two unrelated parents: just inherit both of them. Declaring a class Platypus(Mammal, Bird) provides all the functionality needed, but can produce ambiguity between properties of the class with the same name between the two parents. Additionally, when properties for an object are initialized, there will be only one initializer defined for the child class, which will need to have knowledge of the initializer definitions for each of its parents. Still, with a defined order for method resolution and proper initialization, this can work without code duplication or a great deal of framework code.

Dependency Injection

With a dependency injection approach, rather than inheriting behavior from a parent class, objects have a collection of components that they can refer to methods or properties of as needed in order to implement their behavior. This adds flexibility by allowing you to pass a full initialized object as a dependency for a new object, and allows you to implement multiple components matching the same interface for a dependency with different implementations to customize behavior. However, this approach doesn’t produce the same outcomes as inheritance as the methods of the components are not available on the composed object unless you define pass-through methods to call the appropriate component. It also breaks is-a relationships for type checks if those are needed in your application.

Compositional Inheritance

What if we combine the multiple inheritance and dependency injection approaches? That way you can have a class adhering to an interface you need (as in the case of inherited methods being available on the object) and provide a default implementation of the interface by an injected component. I have created a basic implementation of Python decorators here: compositional_inheritance.py that combines these approaches by accepting additional constructor arguments on any decorated class for components matching interfaces while also adding passthrough method definitions for each method available on the components. This way each component retains its own data, can be replaced with alternate components for customization, and exposes the behavior we need on the composed class.

Here is what the platypus example would look like with this approach:

class EggLaying:

def lay(self):

print("laid egg")

class Fuzzy:

def pet(self):

print("petting fuzzy animal, aw...")

@components(EggLaying, Fuzzy)

class Platypus:

pass # No code duplication! :)With the simple example we’ve been working with, this is identical to a multiple inheritance, because the component classes don’t have conflicting properties and we don’t need to switch out any of the components. Here’s a slightly more detailed example with multiple levels of components and swapping components to customize behavior:

class Moveable:

def move(self):

return "walks"

class Swimming:

def move(self):

return "swims"

class Flying:

def move(self):

return "flies"

class Feedable:

def feed(self):

return "eats meat"

@components(Moveable, Feedable)

class Animal:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def describe(self):

print(f"{self.name} is an animal that {self.move()} and {self.feed()}")

something = Animal("default")

something.describe()

@components((Animal, ["shark"], {'_component_Moveable': Swimming()}))

class Shark:

pass

shark = Shark()

shark.describe()

sharknado = Shark(_component_Animal=Animal("sharknado", _component_Moveable=Flying()))

sharknado.describe()

# In some cases, you can create objects that would otherwise need a new subclass with just a new component

@components(Feedable)

class Laser:

def feed(self):

return self._component_Feedable.feed() + "... *fried*"

laser_sharknado = Shark(_component_Animal=Animal("laser_sharknado", _component_Moveable=Flying(), _component_Feedable=Laser()))

laser_sharknado.describe()